The Remarkable Decline of Homophobia

This article is an excerpt from the manuscript of Probably Overthinking It, available from the University of Chicago Press and from Amazon and, if you want to support independent bookstores, from Bookshop.org.

[This excerpt is from a chapter on moral progress. Previous examples explored responses to survey questions related to race and gender.]

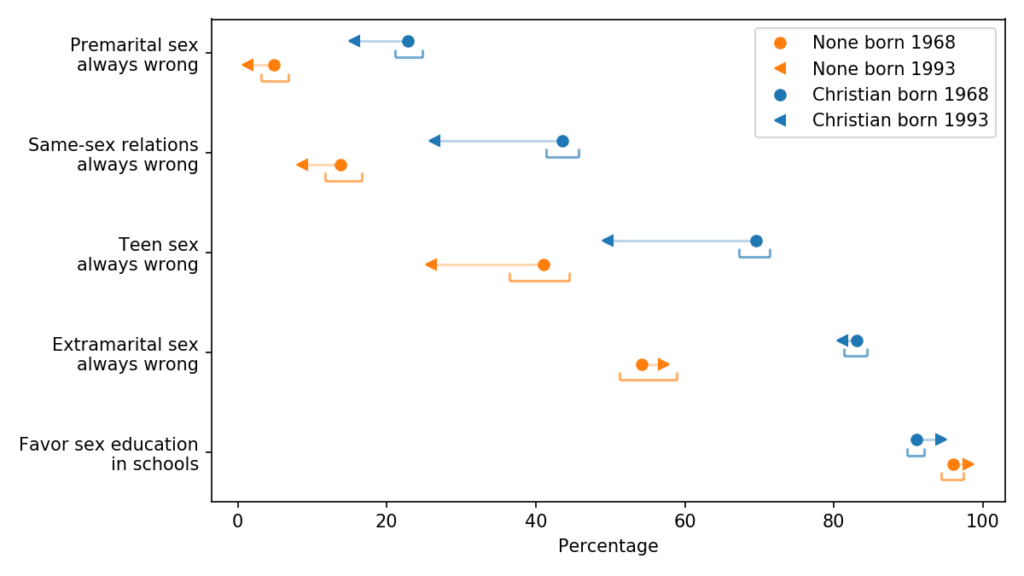

The General Social Survey includes four questions related to sexual orientation.

- What about sexual relations between two adults of the same sex – do you think it is always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?

- And what about a man who admits that he is a homosexual? Should such a person be allowed to teach in a college or university, or not?

- If some people in your community suggested that a book he wrote in favor of homosexuality should be taken out of your public library, would you favor removing this book, or not?

- Suppose this admitted homosexual wanted to make a speech in your community. Should he be allowed to speak, or not?

If the wording of these questions seems dated, remember that they were written around 1970, when one might “admit” to homosexuality, and a large majority thought it was wrong, wrong, or wrong. In general, the GSS avoids changing the wording of questions, because subtle word choices can influence the results. But the price of this consistency is that a phrasing that might have been neutral in 1970 seems loaded today.

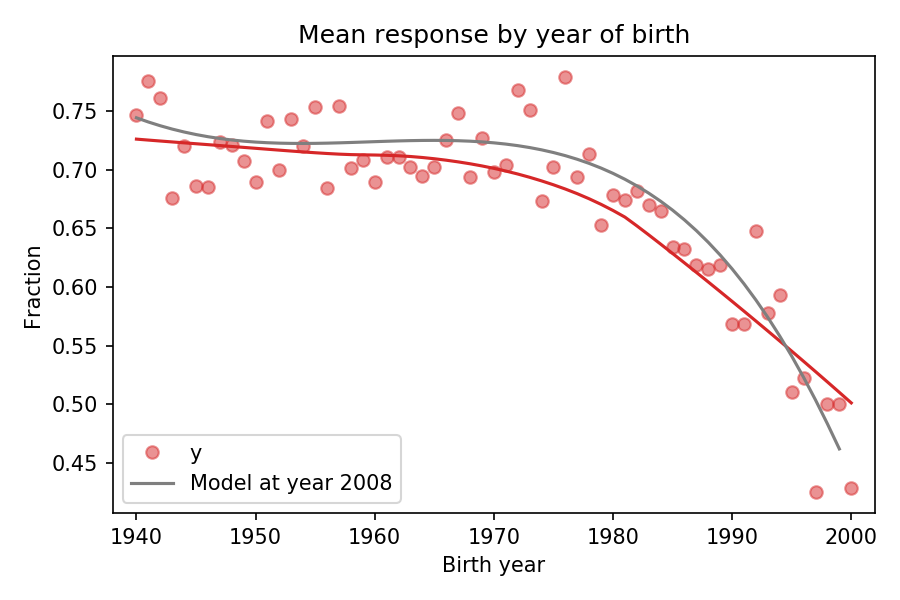

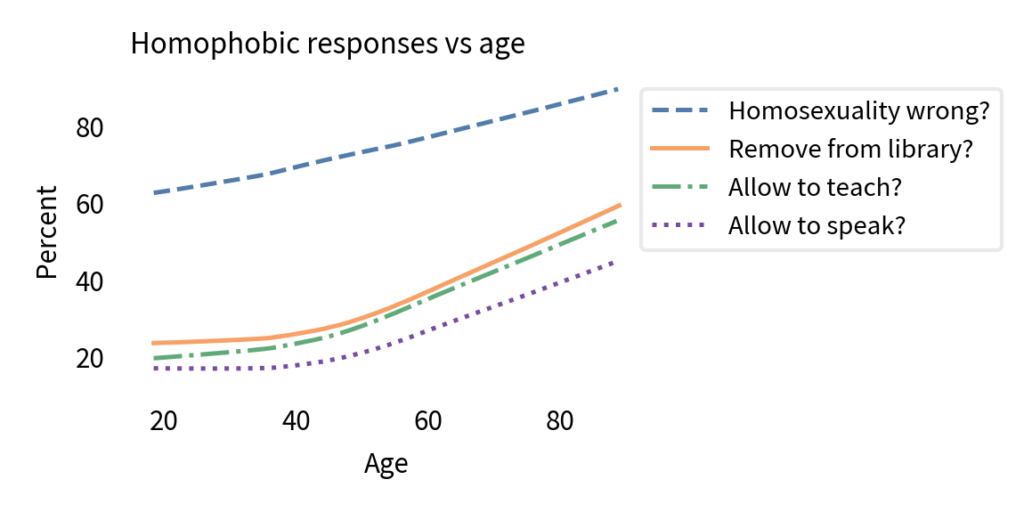

Nevertheless, let’s look at the results. The following figure shows the percentage of people who chose a homophobic response to these questions as a function of age.

It comes as no surprise that older people are more likely to hold homophobic beliefs. But that doesn’t mean people adopt these attitudes as they age. In fact, within every birth cohort, they become less homophobic with age.

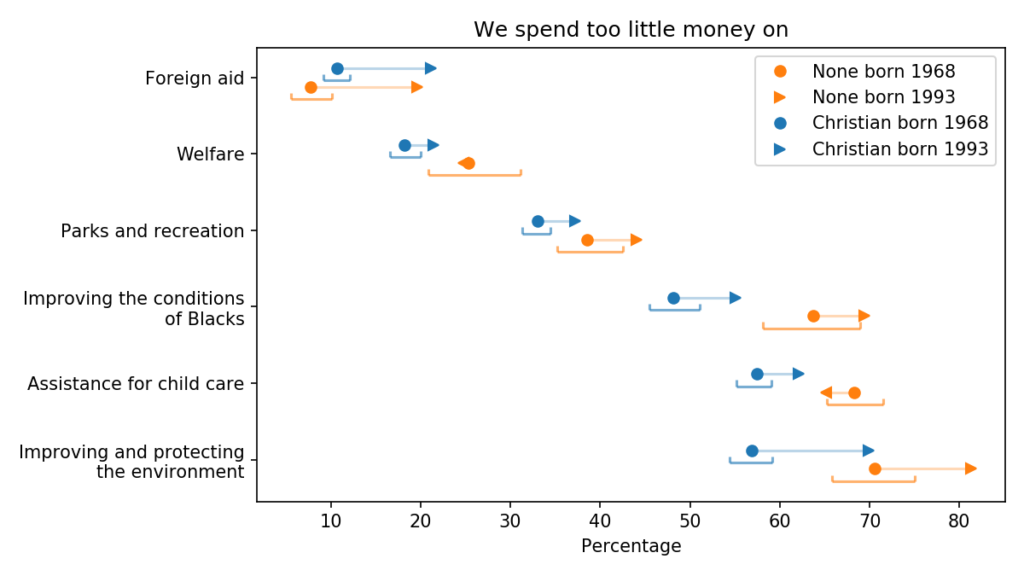

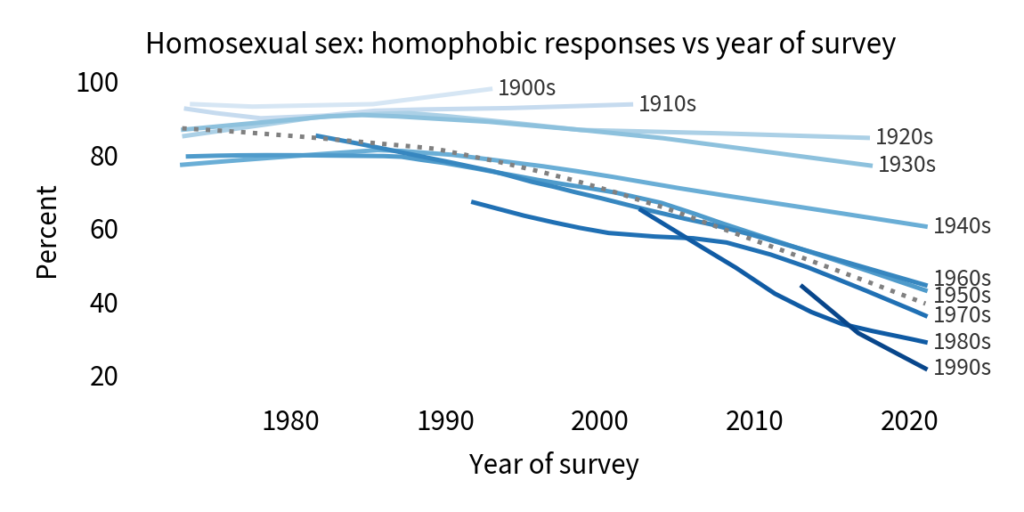

The following figure show the results from the first question, showing the percentage of respondents who said homosexuality was wrong (with or without an adverb).

There is clearly a cohort effect: each generation is substantially less homophobic than the one before. And in almost every cohort, homophobia declines with age. But that doesn’t mean there is an age effect; if there were, we would expect to see a change in all cohorts at about the same age. And there’s no sign of that.

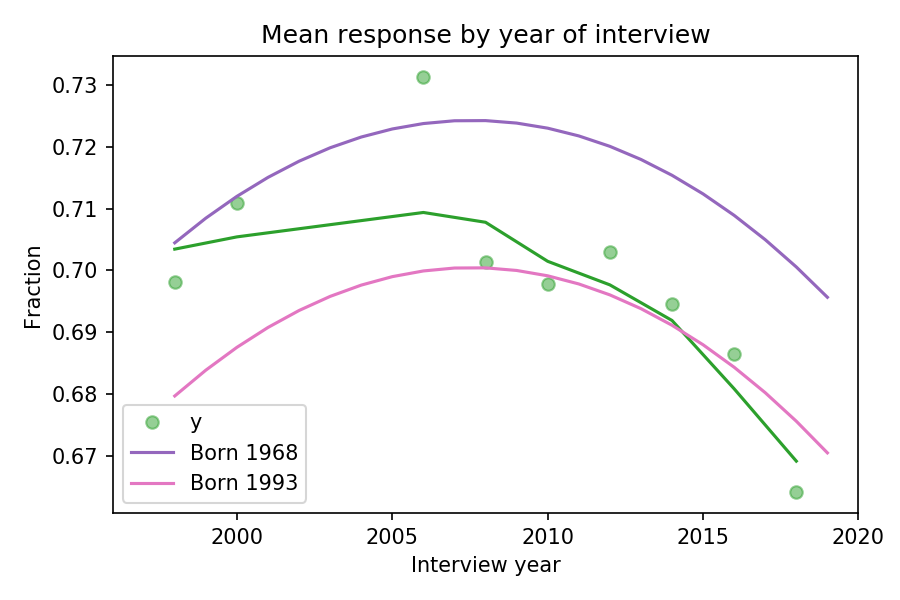

So let’s see if it might be a period effect. The following figure shows the same results plotted over time rather than age.

If there is a period effect, we expect to see an inflection point in all cohorts at the same point in time. And there is some evidence of that. Reading from top to bottom:

- More than 90% of people born in the nineteen-oughts and the teens thought homosexuality was wrong, and they went to their graves without changing their minds.

- People born in the 1920s and 1930s might have softened their views, slightly, starting around 1990.

- Among people born in the 1940s and 1950s, there is a notable inflection point: before 1990, they were almost unchanged; after 1990, they became more tolerant over time.

- In the last four cohorts, there is a clear trend over time, but we did not observe these groups sufficiently before 1990 to identify an inflection point.

On the whole, this looks like a period effect. Also, looking at the overall trend, it declined slowly before 1990 and much more quickly thereafter. So we might wonder what happened in 1990.

What happened in 1990?

In general, questions like this are hard to answer. Societal changes are the result of interactions between many causes and effects. But in this case, I think there is an explanation that is at least plausible: advocacy for acceptance of homosexuality has been successful at changing people’s minds.

In 1989, Marshall Kirk and Hunter Madsen published a book called After the Ball with the prophetic subtitle How America Will Conquer Its Fear and Hatred of Gays in the ’90s. The authors, with backgrounds in psychology and advertising, outlined a strategy for changing beliefs about homosexuality, which I will paraphrase in two parts: make homosexuality visible, and make it boring. Toward the first goal, they encouraged people to come out and acknowledge their sexual orientation publicly. Toward the second, they proposed a media campaign to depict homosexuality as ordinary.

Some conservative opponents of gay rights latched onto this book as a textbook of propaganda and the written form of the “gay agenda”. Of course reality was more complicated than that: social change is the result of many people in many places, not a centrally-organized conspiracy.

It’s not clear whether Kirk and Madsen’s book caused America to conquer its fear in the 1990s, but what they proposed turned out to be a remarkable prediction of what happened. Among many milestones, the first National Coming Out Day was celebrated in 1988; the first Gay Pride Day Parade was in 1994 (although previous similar events had used different names); and in 1999, President Bill Clinton proclaimed June as Gay and Lesbian Pride month.

During this time, the number of people who came out to their friends and family grew exponentially, along with the number of openly gay public figures and the representation of gay characters on television and in movies.

And as surveys by the Pew Research Center have shown repeatedly, “familiarity is closely linked to tolerance”. People who have a gay friend or family member – and know it – are substantially more likely to hold positive attitudes about homosexuality and to support gay rights.

All of this adds up to a large period effect that has changed hearts and minds, especially among the most recent birth cohorts.

Cohort or period effect?

Since 1990, attitudes about homosexuality have changed due to

- A cohort effect: As old homophobes die, they are replaced by a more tolerant generation.

- A period effect: Within most cohorts, people became more tolerant over time.

These effects are additive, so the overall trend is steeper than the trend within the cohorts – like Simpson’s paradox in reverse. But that raises a question: how much of the overall trend is due to the cohort effect, and how much to the period effect?

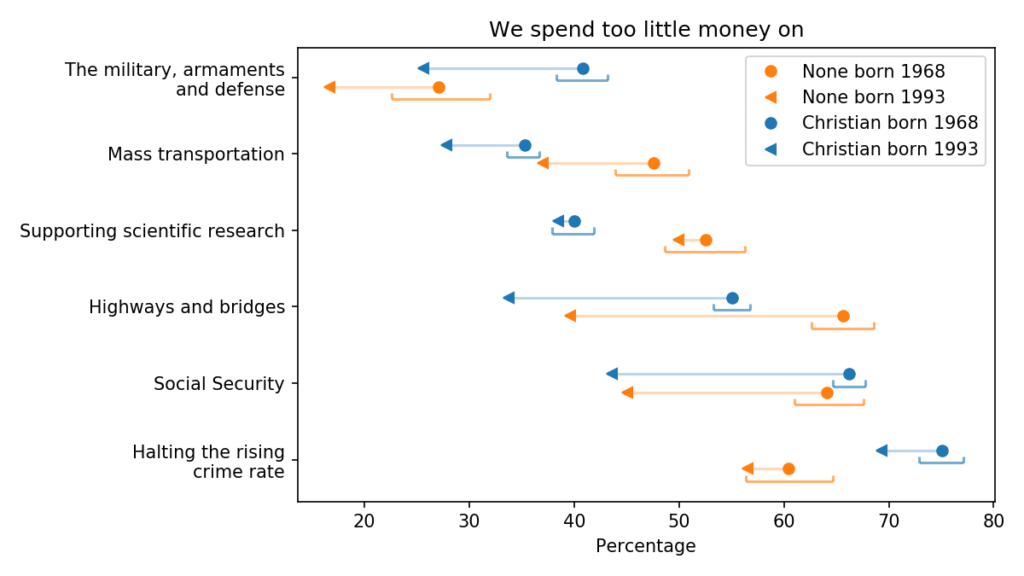

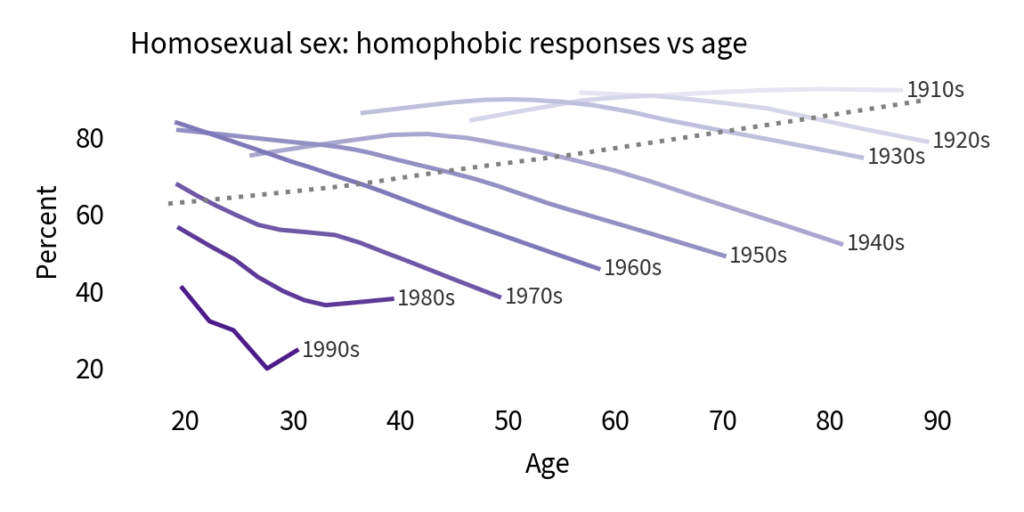

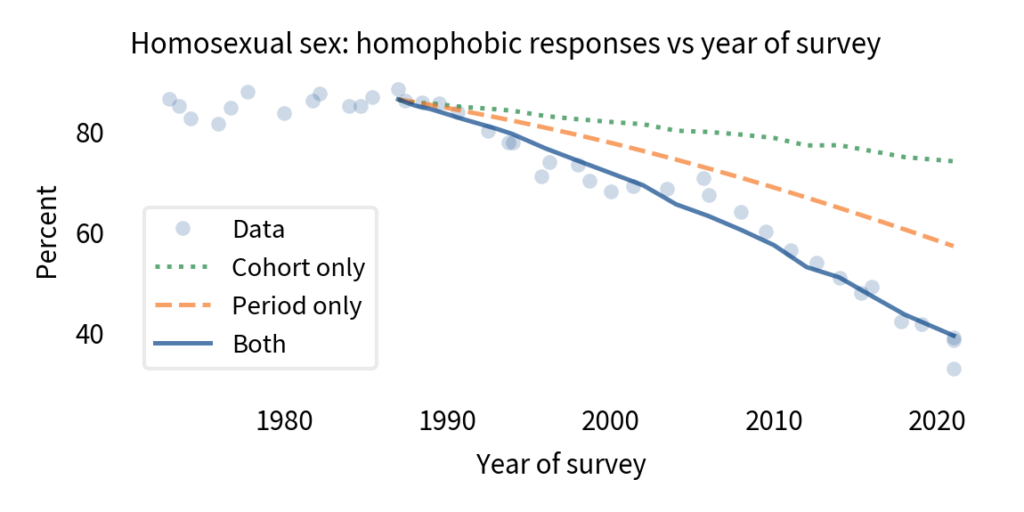

To answer that, I used a model that estimates the contributions of the two effects separately (a logistic regression model, if you want the details). Then I used the model to generate predictions for two counterfactual scenarios: what if there had been no cohort effect, and what if there had been no period effect? The following figure shows the results.

The circles show the actual data. The solid line shows the results from the model from 1987 to 2018, including both effects. The model plots a smooth course through the data, which confirms that it captures the overall trend during this interval. The total change is about 46 percentage points.

The dotted line shows what would have happened, according to the model, if there had been no period effect; the total change due to the cohort effect alone would have been about 12 percentage points.

The dashed line shows what would have happened if there had been no cohort effect; the total change due to the period effect alone would have been about 29 percentage points.

You might notice that the sum of 12 and 29 is only 41, not 46. That’s not an error; in a model like this, we don’t expect percentage points to add up (because it’s linear on a logistic scale, not a percentage scale).

Nevertheless, we can conclude that the magnitude of the period effect is about twice the magnitude of the cohort effect. In other words, most of the change we’ve seen since 1987 has been due to changed minds, with the smaller part due to generational replacement.

No one knows that better than the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus. In July 2021, they performed a song by Tim Rosser and Charlie Sohne with the title, “A Message From the Gay Community”. It begins:

To those of you out there who are still working against equal rights, we have a message for you […]

You think that we’ll corrupt your kids, if our agenda goes unchecked.

Funny, just this once, you’re correct.

We’ll convert your children, happens bit by bit;

Quietly and subtly, and you will barely notice it.

Of course, the reference to the “gay agenda” is tongue-in-cheek, and the threat to “convert your children” is only scary to someone who thinks (wrongly) that gay people can convert straight people to homosexuality, and believes (wrongly) that having a gay child is bad. For everyone else, it is clearly a joke.

Then the refrain delivers the punchline:

We’ll convert your children; we’ll make them tolerant and fair.

For anyone who still doesn’t get it, later verses explain:

Turning your children into accepting, caring people;

We’ll convert your children; someone’s gotta teach them not to hate.

Your children will care about fairness and justice for others.

And finally,

Your kids will start converting you; the gay agenda is coming home.

We’ll convert your children; and make an ally of you yet.

The thesis of the song is that advocacy can change minds, especially among young people. Those changed minds create an environment where the next generation is more likely to be “tolerant and fair”, and where some older people change their minds, too.

The data show that this thesis is, “just this once, correct”.

Sources

- The General Social Survey (GSS) is a project of the independent research organization NORC at the University of Chicago, with principal funding from the National Science Foundation. The data is available from the GSS website.

- The Pew Research study showing that familiarity breeds acceptance is “Four-in-Ten Americans Have Close Friends or Relatives Who are Gay”.

- You can see a performance of “A Message From the Gay Community” on YouTube.