What size is that correlation?

This article is related to Chapter 6 of Probably Overthinking It, which is available for preorder now. It is also related to a new course at Brilliant.org, Explaining Variation.

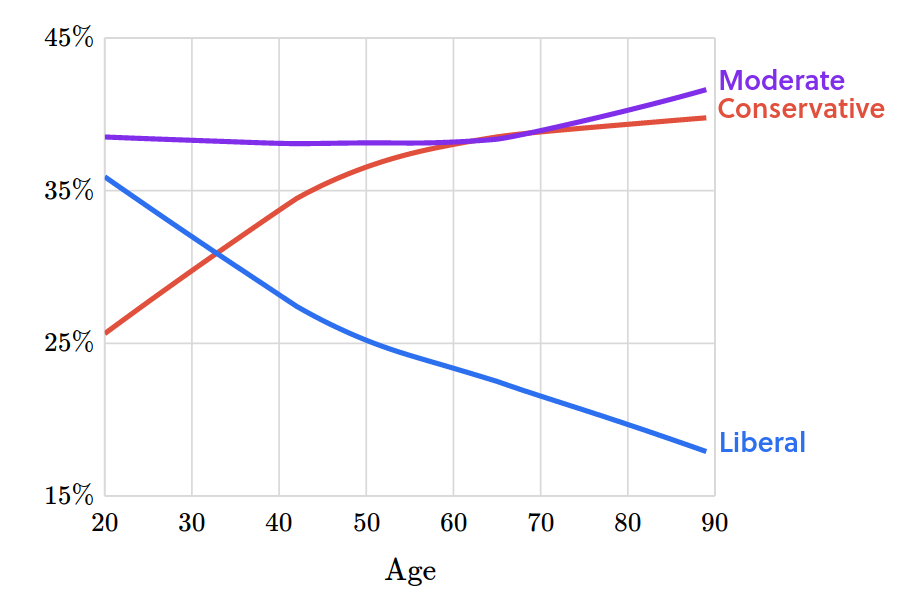

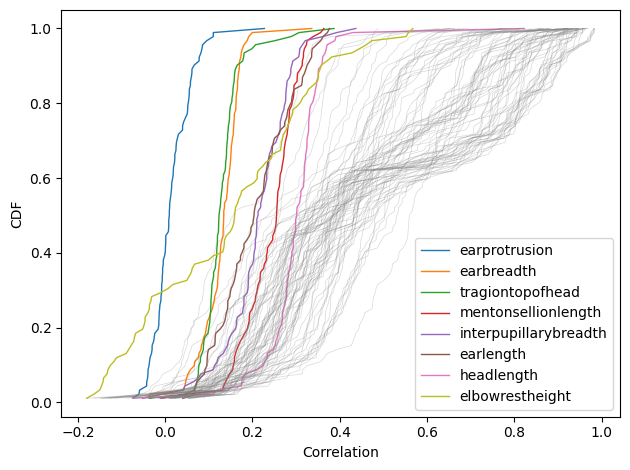

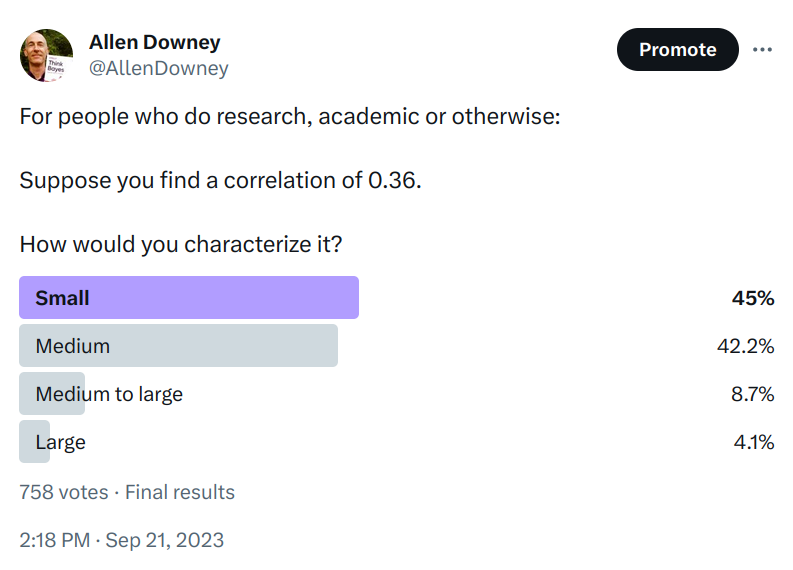

Suppose you find a correlation of 0.36. How would you characterize it? I posed this question to the stalwart few still floating on the wreckage of Twitter, and here are the responses.

It seems like there is no agreement about whether 0.36 is small, medium, or large. In the replies, nearly everyone said it depends on the context, and of course that’s true. But there are two things they might mean, and I only agree with one of them:

- In different areas of research, you typically find correlations in difference ranges, so what’s “small” in one field might be “large” in another.

- It depends on the goal of the project — that is, what you are trying to predict, explain, or decide.

The first interpretation is widely accepted in the social sciences. For example, this highly-cited paper proposes as a guideline that, “an effect-size r of .30 indicates an effect that is large and potentially powerful in both the short and the long run.” This guideline is offered in light of “the average sizes of effects in the published literature of social and personality psychology.”

I don’t think that’s a good argument. If you study mice, and you find a large mouse, that doesn’t mean you found an elephant.

But the same paper offers what I think is better advice: “Report effect sizes in terms that are

meaningful in context”. So let’s do that.

What is the context?

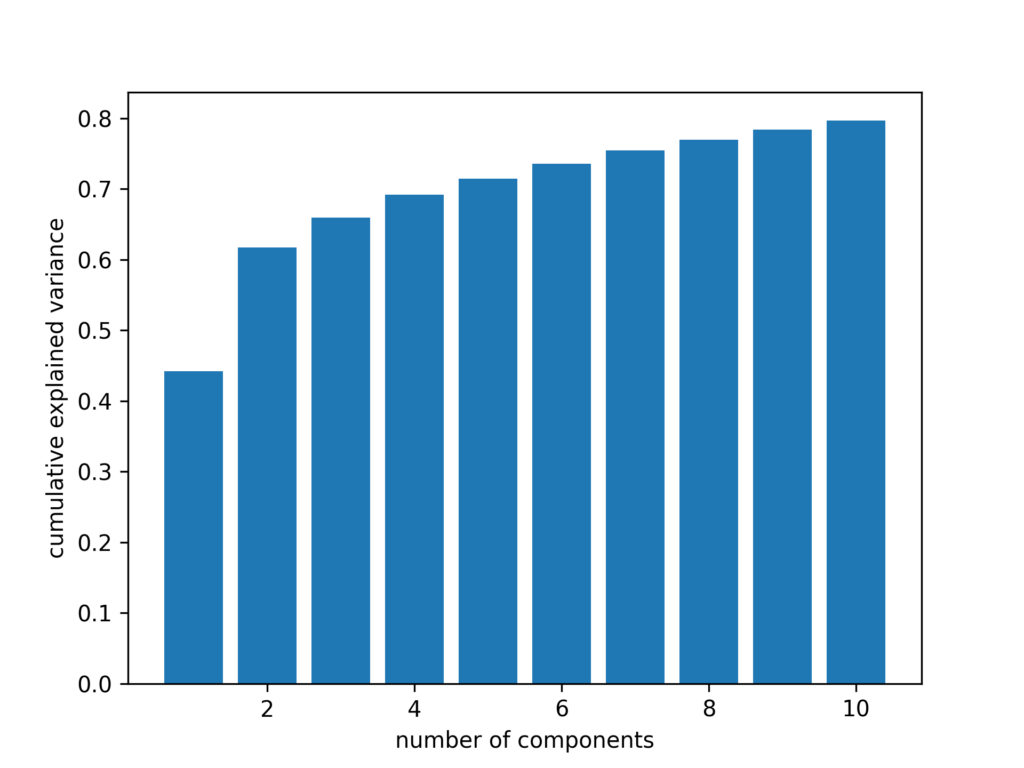

I asked about r = 0.36 because that’s the correlation between general mental ability (g) and the general factor of personality (GFP) reported in this paper, which reports meta-analyses of correlations between a large number of cognitive abilities and personality traits.

Now, for purposes of this discussion, you don’t have to believe that g and GFP are valid measures of stable characteristics. Let’s assume that they are — if you are willing to play along — just long enough to ask: if the correlation between them is 0.36, what does that mean?

I propose that the answer depends on whether we are trying to make a prediction, explain a phenomenon, or make decisions that have consequences. Let’s take those in turn.

Prediction

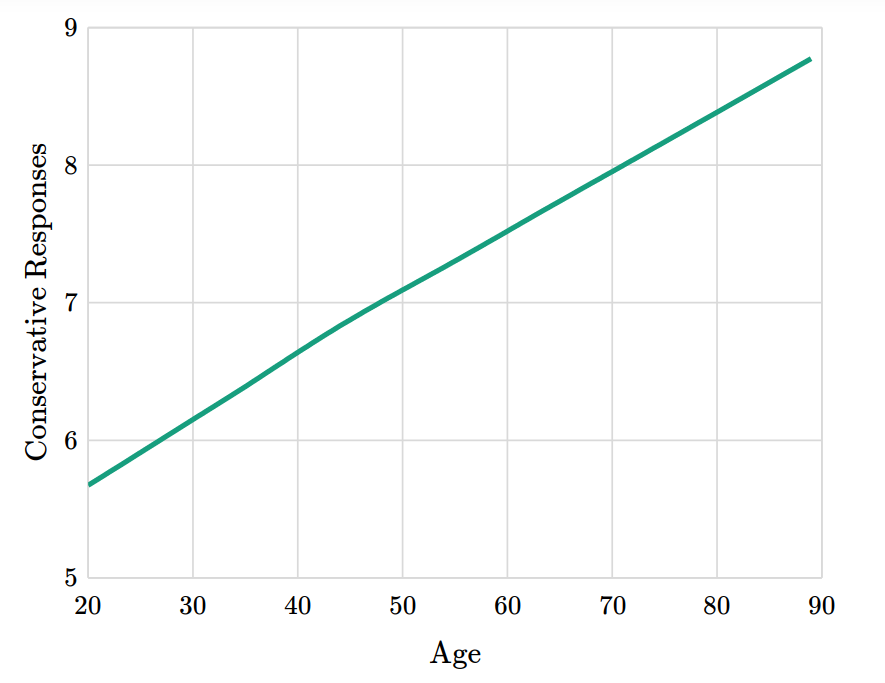

Thinking about correlation in terms of predictive value, let’s assume that we can measure both g and GFP precisely, and that both are expressed as standardized scores with mean 0 and standard deviation 1. If the correlation between them is 0.36, and we know that someone has g=1 (one standard deviation above the mean), we expect them to have GFP=0.36 (0.36 standard deviations above the mean), on average.

In terms of percentiles, someone with g=1 is in the 84th percentile, and we would expect their GFP to be in the 64th percentile. So in that sense, g conveys some information about GFP, but not much.

To quantify predictive accuracy, we have several metrics to choose from — I’ll use mean absolute error (MAE) because I think is the most interpretable metric of accuracy for a continuous variable. In this scenario, if we know g exactly, and use it to predict GFP, the MAE is 0.75, which means that we expect to be off by 0.75 standard deviations, on average.

For comparison, if we don’t know g, and we are asked to guess GFP, we expect to be off by 0.8 standard deviations, on average. Compared to this baseline, knowing g reduces MAE by about 6%. So a correlation of 0.36 doesn’t improve predictive accuracy by much, as I discussed in this previous blog post.

Another metric we might consider is classification accuracy. For example, suppose we know that someone has g>0 — so they are smarter than average. We can compute the probability that they also have GFP>0 — informally, they are nicer than average. This probability is about 0.62.

Again, we can compare this result to a baseline where g is unknown. In that case the probability that someone is smarter than average is 0.5. Knowing that someone is smart moves the needle from 0.5 to 0.62, which means that it contributes some information, but not much.

Going in the other direction, if we think of low g as a risk factor for low GFP, the risk ratio would be 1.2. Expressed as an odds ratio it would be 1.6. In medicine, a risk factor with RR=1.2 or OR=1.6 would be considered a small increase in risk. But again, it depends on context — for a common condition with large health effects, identifying a preventable factor with RR=1.2 could be a very important result!

Explanation

Instead of prediction, suppose you are trying to explain a particular phenomenon and you find a correlation of 0.36 between two relevant variables, A and B. On the face of it, such a correlation is evidence that there is some kind of causal relationship between the variables. But by itself, the correlation gives no information about whether A causes B, B causes A, or any number of other factors cause both A and B.

Nevertheless, it provides a starting place for a hypothetical question like, “If A causes B, and the strength of that causal relationship yields a correlation of 0.36, would that be big enough to explain the phenomenon?” or “What part of the phenomenon could it explain?”

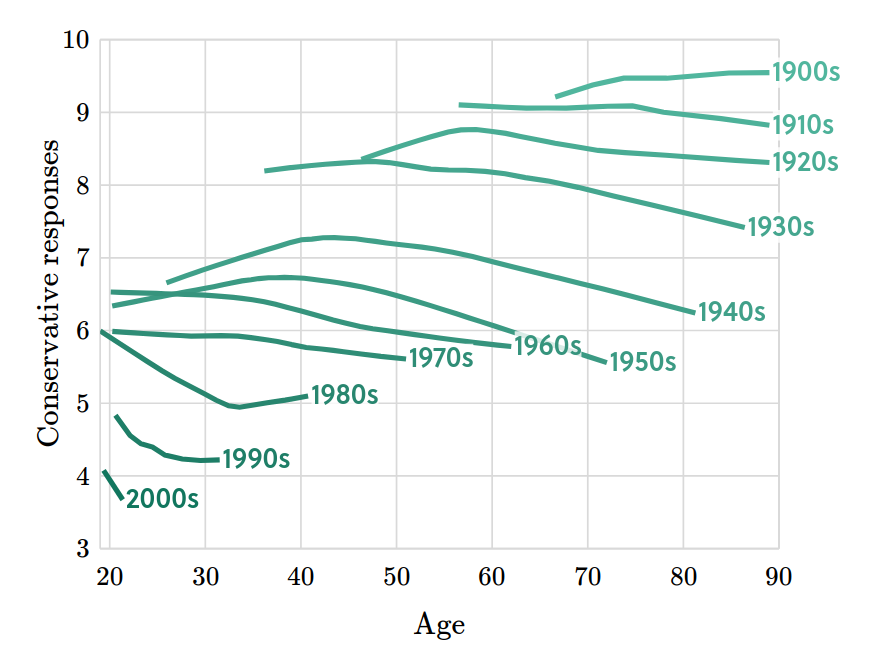

As an example, let’s consider the article that got me thinking about this, which proposes in the title the phenomenon it promises to explain: “Smart, Funny, & Hot: Why some people have it all…”

Supposing that “smart” is quantified by g and that “funny” and other positive personality traits are quantified by GFP, and that the correlation between them is 0.36, does that explain why “some people have it all”?

Let’s say that “having it all” means g>1 and GFP>1. If the factors were uncorrelated, only 2.5% of the population would exceed both thresholds. With correlation 0.36, it would be 5%. So the correlation could explain why people who have it all are about twice as common as they would be otherwise.

Again, you don’t have to buy any part of this argument, but it is an example of how an observed correlation could explain a phenomenon, and how we could report the effect size in terms that are meaningful in context.

Decision-making

After prediction and explanation, a third use of an observed correlation is to guide decision-making.

For example, in a 2106 article, ProPublic evaluated COMPAS, an algorithm used to inform decisions about bail and parole. They found that its classification accuracy was 0.61, which they characterized as “somewhat better than a coin toss”. For decisions that affect people’s lives in such profound ways, that accuracy is disturbingly low.

But in another context, “somewhat better than a coin toss” can be a big deal. In response to my poll about a correlation of 0.36, one stalwart replied, “In asset pricing? Say as a signal of alpha? So implausibly large as to be dismissed outright without consideration.”

If I understand correctly, this means that if you find a quantity known in the present that correlates with future prices with r = 0.36, you can use that information to make decisions that are substantially better than chance and outperform the market. But it is extremely unlikely that such a quantity exists.

However, if you make a large number of decisions, and the results of those decisions accumulate, even a very small correlation can yield a large effect. The paper I quoted earlier makes a similar observation in the context of individual differences:

“If a psychological process is experimentally demonstrated, and this process is found to appear reliably, then its influence could in many cases be expected to accumulate into important implications over time or across people even if its effect size is seemingly small in any particular instance.”

I think this point is correct, but incomplete. If a small effect accumulates, it can yield big differences, but if that’s the argument you want to make, you have to support it with a model of the aggregation process that estimates the cumulative effect that could result from the observed correlation.

Predict, Explain, Decide

Whether a correlation is big or small, important or not, and useful or not, depends on the context, of course. But to be more specific, it depends on whether you are trying to predict, explain, or decide. And what you report should follow:

- If you are making predictions, report a metric of predictive accuracy. For continuous quantities, I think MAE is most interpretable. For discrete values, report classification accuracy — or recall and precision, or AUC.

- If you are explaining a phenomenon, use a model to show whether the effect you found is plausibly big enough to explain the phenomenon, or what fraction it could explain.

- If you are making decisions, use a model to quantify the expected benefit — or the distribution of benefits would be even better. If your argument is that small correlations accumulate into big effects, use a model to show how and quantify how much.

As an aside, thinking of modeling in terms of prediction, explanation, and decision-making is the foundation of Modeling and Simulation in Python, now available from No Starch Press and Amazon.com.