Young Adults Want Fewer Children

The most recent data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) provides a first look at people born in the 2000s as young adults and an updated view of people born in the 1990s at the peak of their child-bearing years. Compared to previous generations at the same ages, these cohorts have fewer children, and they are less likely to say they intend to have children. Unless their plans change, trends toward lower fertility are likely to continue for the next 10-20 years.

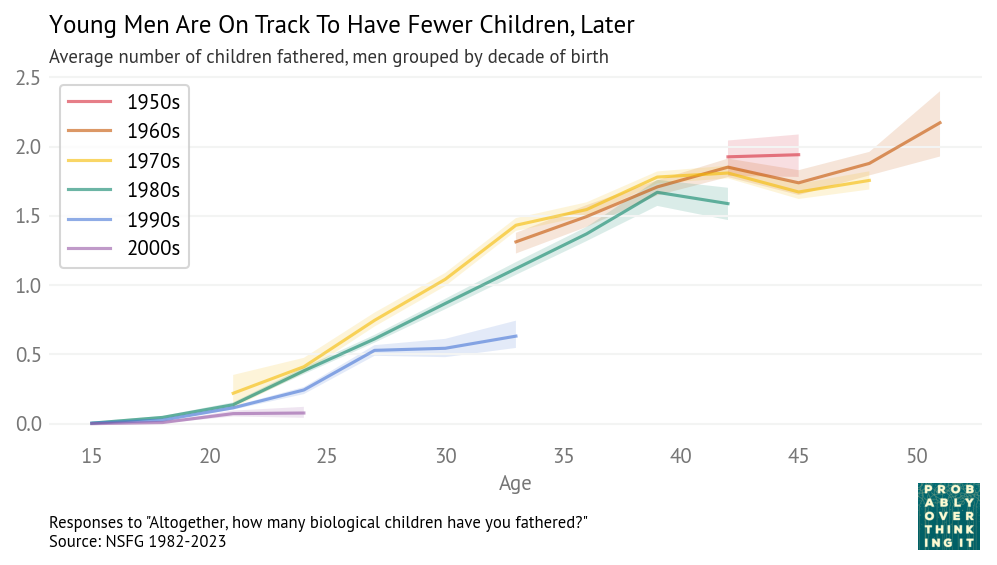

The following figure shows the number of children fathered by male respondents as a function of their age when interviewed, grouped by decade of birth. It includes the most recent data, collected in 2022-23, combined with data from previous iterations of the survey going back to 1982.

Men born in the 1990s and 2000s have fathered fewer children than previous generations at the same ages:

- At age 33, men born in the 1990s (blue line) have 0.6 children on average, compared to 1.1 – 1.4 in previous cohorts.

- At age 24, men born in the 2000s (violet line) have 0.1 children on average, compared to 0.2 – 0.4 in previous cohorts.

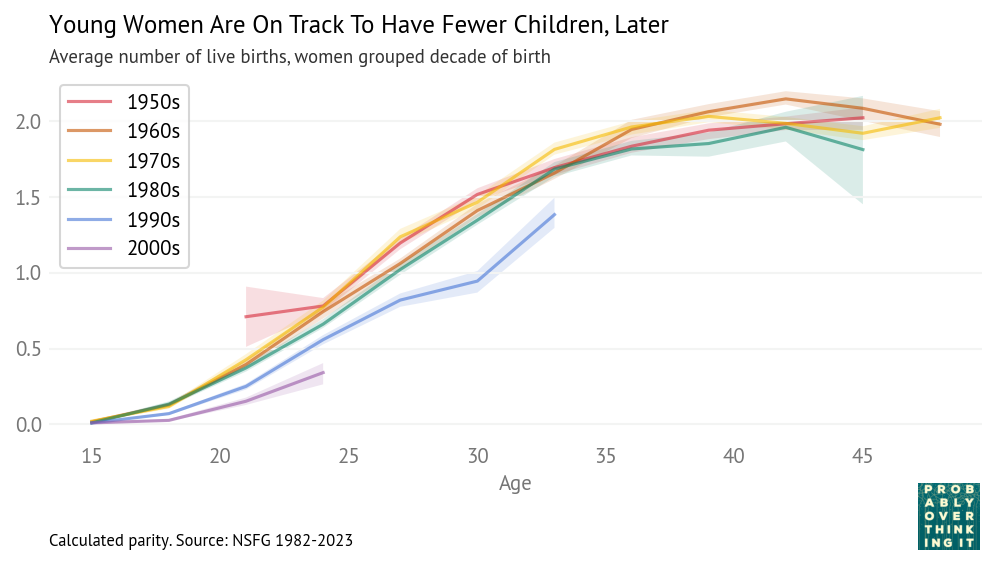

The pattern is similar for women.

Women born in the 1990s and 2000s are having fewer children, later, than previous generations.

- At age 33, women in the 1990s cohort have 1.4 children on average, compared to 1.7 – 1.8 in previous cohorts.

- At age 24, women in the 2000s cohort have 0.3 children on average, compared to 0.6 – 0.8 in previous cohorts.

Desires and Intentions

The NSFG asks respondents whether they want to have children and whether they intend to. These questions are useful because they distinguish between two possible causes of declining fertility. If someone says they want a child, but don’t intend to have one, it seems like something is standing in their way. In that case, changing circumstances might change their intentions. But if they don’t want children, that might be less likely to change.

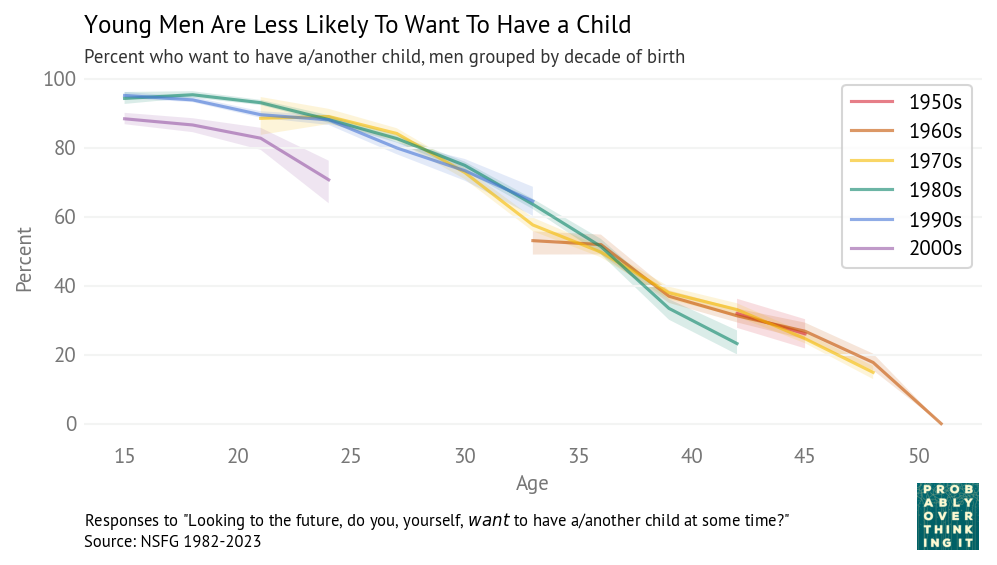

Let’s start with stated desires. The following figure shows the fraction of men who say they want a child — or another child if they have at least one — grouped by decade of birth.

Men born in the 2000s are less likely to say they want to have a child — about 86% compared to 92% in previous cohorts. Men born in the 1990s are indistinguishable from previous cohorts.

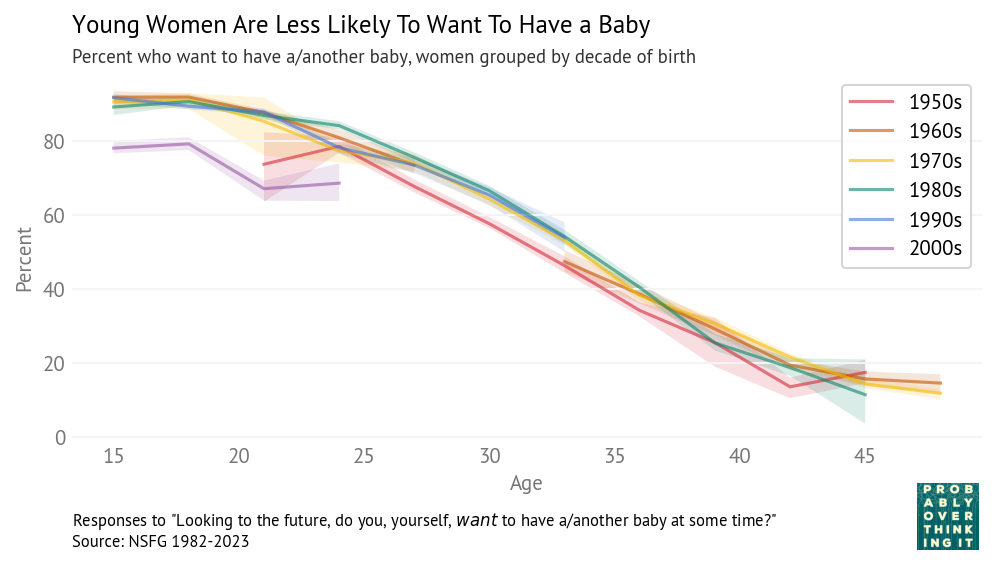

The pattern is similar for women — the following figure shows the fraction who say they want a baby, grouped by decade of birth.

Women born in the 2000s are less likely to say they want a baby — about 76%, compared to 87% for previous cohorts when they were interviewed at the same ages. Women born in the 1990s are in line with previous generations.

Maybe surprisingly, men are more likely to say they want children. For example, of young men (15 to 24) born in the 2000s, 86% say they want children, compared to 76% of their female peers. Lyman Stone wrote about this pattern recently.

What About Intentions?

The patterns are similar when people are asked whether they intend to have a child. Men and women born in the 1990s are indistinguishable from previous generations, but

- Men born in the 2000s are less likely to say they intend to have a child — about 80% compared to 85–86% in previous cohorts at the same ages (15 to 24).

- Women born in the 2000s are less likely to say they intend to have a child — about 69% compared to 80–82% in previous cohorts.

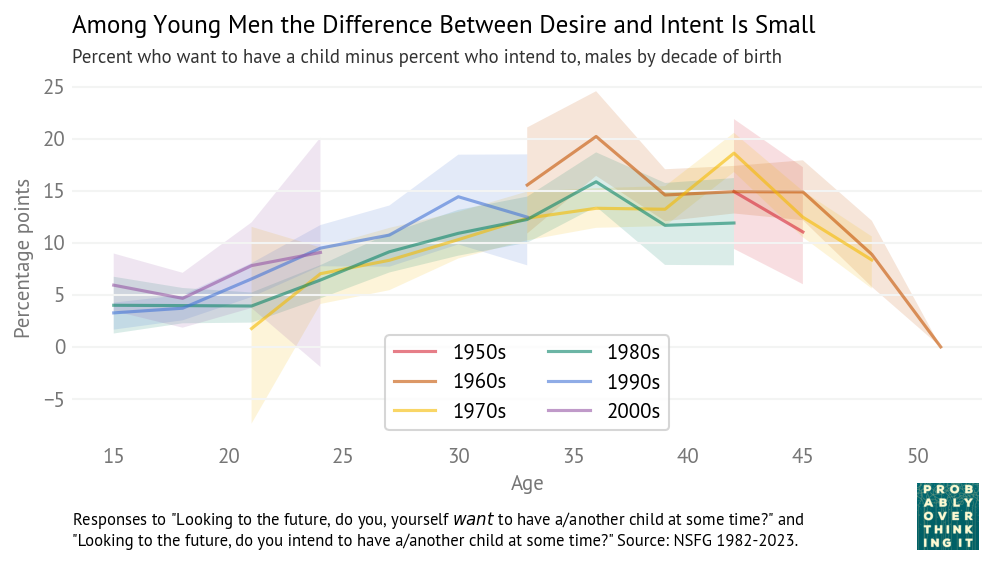

Now let’s look more closely at the difference between wants and intentions. The following figure shows the percentage of men who want a child minus the percentage who intend to have a child.

Among young men, the difference is small — most people who want a child intend to have one. The difference increases with age. Among men in their 30s, a substantial number say they would like another child but don’t intend to have one.

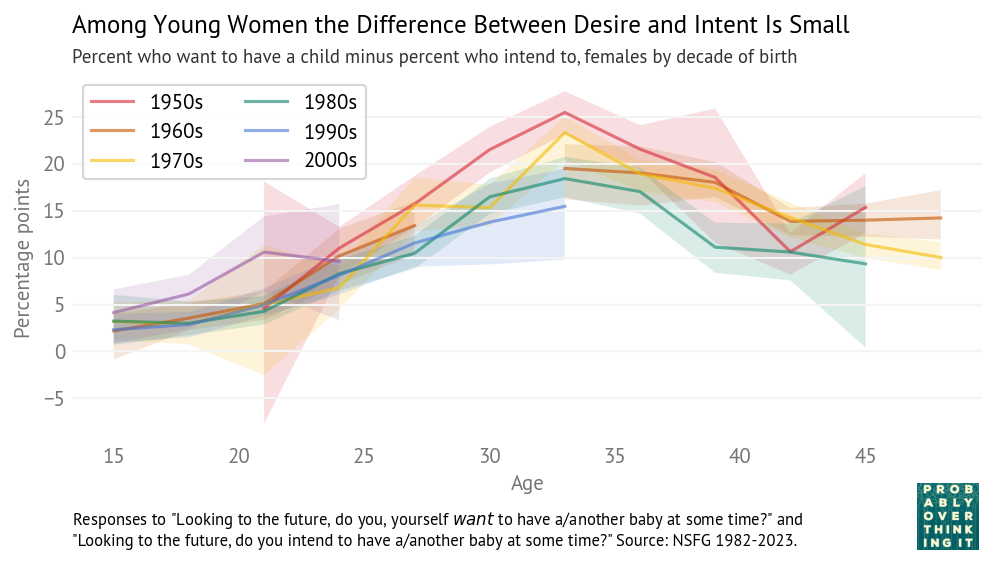

Here are the same differences for women.

The patterns are similar — among young women, most who want a child intend to have one. Among women in their 30s, the gap sometimes exceeds 20 percentage points, but might be decreasing in successive generations.

These results suggest that fertility is lower among people born in the 1990s and 2000s — at least so far — because they want fewer children, not because circumstances prevent them from having the children they want.

From the point of view of reproductive freedom, that conclusion is better than an alternative where people want children but can’t have them. But from the perspective of public policy, these results suggest that reversing these trends would be difficult: removing barriers is relatively easy — changing what people want is generally harder.

DATA NOTE: In the most recent iteration of the NSFG, about 75% of respondents were surveyed online; the other 25% were interviewed face-to-face, as all respondents were in previous iterations. Changes like this can affect the results, especially for more sensitive questions. And in the NSFG, Lyman Stone has pointed out that there are non-negligible differences when we compare online and face-to-face responses. Specifically, people who responded online were less likely to say they want children and less likely to say they intend to have children. At first consideration, it’s possible that these differences could be due to social desirability bias.

However, people who responded online also reported substantially lower parity (women) and number of biological children (men), on average, than people interviewed face-to-face — and it is much less likely that these responses depend on interview format. It is more likely that the way respondents were assigned to different formats depended on parity/number of children, and that difference explains the observed differences in desire and intent for more children. Since there is no strong evidence that the change in format accounts for the differences we see, I’m taking the results at face value for now.