Young Christians are more sex-positive than the previous generation

This is the fifth and probably final in a series of articles where I use data from the General Social Survey (GSS) to explore

- Differences in beliefs and attitudes between Christians and people with no religious affiliation (“Nones”),

- Generational differences between younger and older Christians, and

- Generational differences between younger and older Nones.

In the first article, I looked at changes in religious beliefs and found that younger Christians are more secular in many ways than the previous generation.

In the second article, I looked at views related to law and public policy and found that young Christians are more progressive on most issues than the previous generation.

In the third article, I found that generational differences on most questions related to abortion are small and probably not practically or statistically significant.

In the fourth article, I looked at responses to questions related to priorities and public spending. On many dimensions, younger Christians are moving toward the beliefs of their secular peers, but there are notable exceptions.

In this article, I use the same dataset to explore changes in attitudes related to sex. For details of the methodology, see the first article.

When is sex wrong?

GSS respondents were asked several questions related to their attitudes about sex:

There’s been a lot of discussion about the way morals and attitudes about sex are changing in this country.

- If a man and woman have sex relations before marriage, do you think it is always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?

- What if they are in their early teens, say 14 to 16 years old? In that case, do you think sex relations before marriage are always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?

- What about sexual relations between two adults of the same sex–do you think it is always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?

- What is your opinion about a married person having sexual relations with someone other than the marriage partner–is it always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?

For each of these questions, I count the fraction of respondents who reply “always wrong”.

And I looked at responses to one other sex-related question:

Would you be for or against sex education in the public schools?

Here are the results:

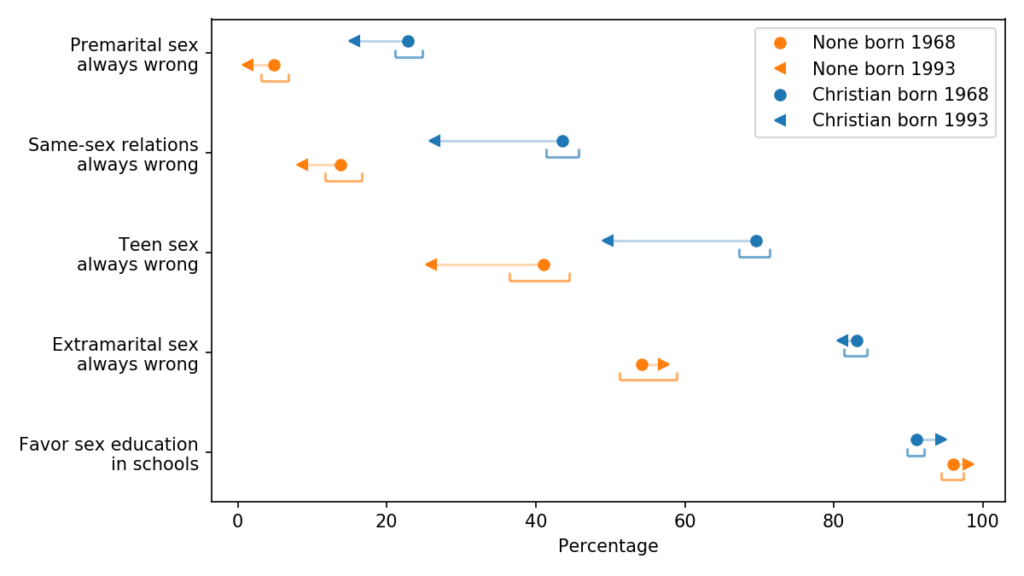

The blue markers are for people whose religious preference is Catholic, Protestant, or Christian; the orange markers are for people with no religious affiliation.

For each group, the circles show estimated percentages for people born in 1968; the arrowheads show percentages for people born in 1993.

For both groups, the estimates are for 2018, when the younger group was 25 and the older group was 50. The brackets show 90% confidence intervals.

In almost every scenario, young Christians are less likely than the previous generation to say that sex is “always wrong”, and in the cases of homosexual and teen sex, the changes are substantial.

Opposition to premarital sex was already low and did not change as much. Support for sex education was already high and is now an overwhelming majority.

The exception is extramarital sex, where there is practically no generational change: more than 80% of both generations think it is always wrong.

Compared to their Christian peers, the non-religious are more sex-positive by 15-30 percentage points. And their generational changes go in the same direction, with young Nones less likely to think sex in these scenarios is wrong.

But again, extramarital sex is the exception; among the Nones, the small generational change is within the margin of error.

This exception suggests that both groups distinguish between actions that harm people and transgressions of divine law.

Summary

In 2007, when I started writing about religious trends, I thought the increasing number of people with no religious affiliation was hugely underreported. Now, the “rise of the Nones” is well known.

Then, for a while, the story was that people were leaving organized religion, but they were still religious or at least spiritual; that is, they were “believing without belonging”.

More recently, it has become clear that beliefs and attitudes among the Nones are getting more secular.

In this series of articles, I have looked at changes among the ones who are left behind; that is, the decreasing fraction who identify as Christian. On many dimensions, the pattern is the same: young Christians are more secular than the previous generation.

Responses that follow this pattern include:

- Almost all religious beliefs and activities, except belief in the afterlife.

- Opposition to sex and sex education, except extramarital sex.

- Matters of public policy including the legalization of marijuana, pornography, and euthanasia; support for affirmative action; and opposition to the death penalty and school prayer.

Many questions related to public spending follow the same pattern, with younger Christians generally moving toward positions held by their secular peers; the only substantial exception is mass transportation, which has less support among young people in both groups [although this result is so surprising to me that I need more evidence to be confident it is correct].

The most notable exceptions are opposition to gun control and abortion, which show almost no generational changes. Maybe not coincidentally, these exceptions are probably the most politicized topics among the questions I explored.

In summary, we can describe secularization in the U.S. as the sum of two trends, changes in affiliation and changes in belief. Both trends are moving fast, and they are moving in the same direction, away from religion.