Left, right, part 2

In the previous article, I looked at data from the General Social Survey (GSS) to see how political alignment in the U.S. has changed, on the axis from conservative to liberal, over the last 50 years.

The GSS asks respondents where they place themselves on a 7-point scale from “extremely liberal” (1) to “extremely conservative” (7), with “moderate” in the middle (4).

In the previous article I computed the mean and standard deviation of the responses as a way of quantifying the center and spread of the distribution. But it can be misleading to treat categorical responses as if they were numerical. So let’s see what we can do with the categories.

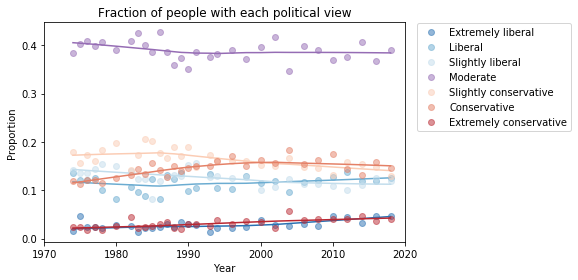

The following plot shows the fraction of respondents who place themselves in each category, plotted over time:

My initial reaction is that these lines are mostly flat. If political alignment is changing in the U.S., it is changing slowly, and the changes might not matter much in practice.

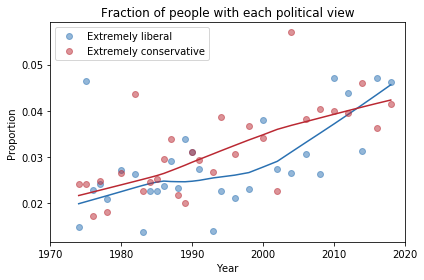

If we look more closely, it seems like the number of people who consider themselves “extreme” is increasing, and the number of moderates might be decreasing. The following plot shows a closer look at the extremes.

There is some evidence of polarization here, but we should not make too much of it. People who consider themselves extreme are still less than 10% of the population, and moderates are still the biggest group, at almost 40%.

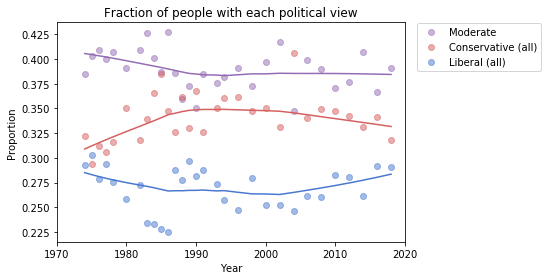

To get a better sense of what’s happening with the other groups, I reduced the number of categories to 3: “Conservative” at any level, “Liberal” at any level, and “Moderate”. Here’s what the plot looks like with these categories:

Moderates make up a plurality; conservatives are the next biggest group, followed by liberals.

From 1974 to 1990, the number of people who call themselves “Conservative” was increasing, but it has decreased ever since. And the number of “Liberals” has been increasing since 2000.

At least, that’s what this plot seems to show. We should be careful about over-interpreting patterns that might be random noise. And we might not want to take these categories too seriously, either.

The hazards of self-reporting

There are several problems with self-reported labels like this.

First, political beliefs are multi-dimensional. “Conservative” and “liberal” are labels for collections of ideas that sometimes go together. But most people hold a mixture of these beliefs.

Also, these labels are relative; that is, when someone says they are conservative, what they often mean is that they are more conservative than the center of the population, or where they think the center is, for the population they have in mind.

Finally, nearly all survey responses are subject to social desirability bias, which is the tendency of people to give answers that make them look better or feel better about themselves.

Over time, the changes we see in these responses depend on actual changes in political beliefs, but they also depend on where the center of the population is, where people think the center is, and the perceived desirability of the labels “liberal”, “conservative”, and “moderate”.

So, in the next article we’ll look more closely at changes in beliefs and attitudes, not just labels.

I am planning to turn these articles into a case study for an upcoming Data Science class, so I welcome comments and questions.

The code I used to generate these figures is in this Jupyter notebook.